Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutWhat does it look like—and is it possible—to be patient-centric at both the individual and population level?

As stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem strive to advance medical value for patients, a central tension arises between value for the individual and value for the population. Depending on your vantage point, this tension can manifest in wholly different goals, success metrics, and frameworks for assessing the value of medical treatments in the U.S.

Health care leaders gathered to discuss what “value” means for patients and populations

To examine this tension and encourage more honest dialogue, Advisory Board hosted its second biennial Cross-Industry Value Summit on November 7-8, 2021. The exclusive gathering convened 30 leaders from across the health care ecosystem, including payers, providers, life sciences, tech, advocacy, and other thought leaders.

Scroll down to learn more about the discussions, participants’ biggest takeaways, and what Advisory Board experts found most surprising.

By Lauren Woodrow

In fall 2019, the Cross-Industry Value Summit solidified its place in Advisory Board mythology. Rumors say the event had real elephants walking around, and the number of lightbulb moments almost caused a fire. This is an event many only ever dream about, and this year I received a coveted invitation.

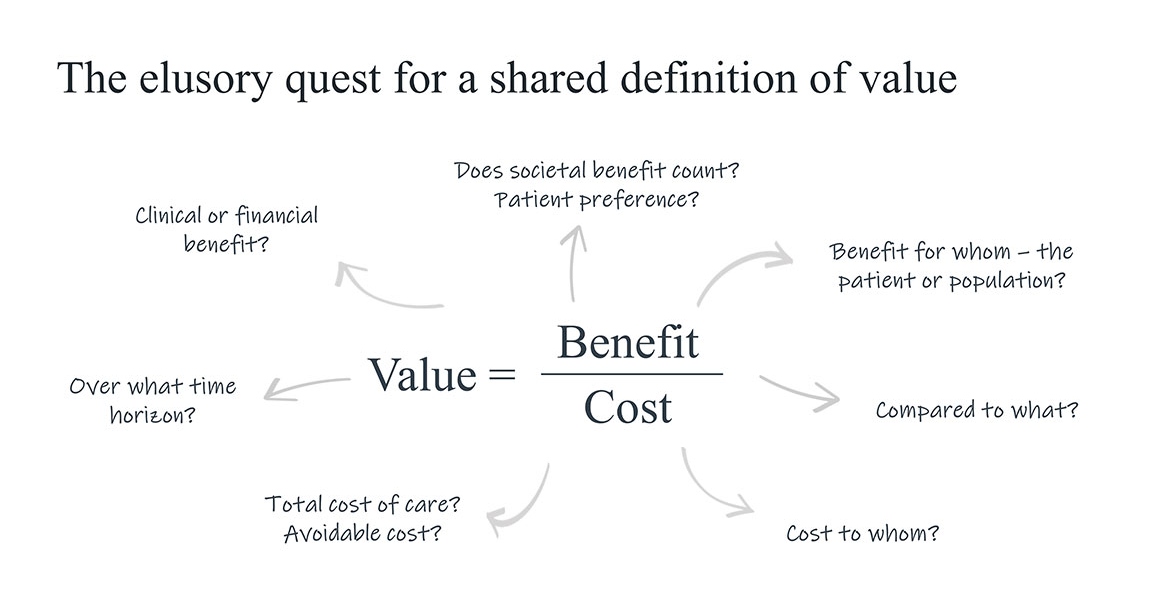

The annual Cross-Industry Value Summit (affectionately known as CIVS) convenes leaders from across the health care industry for a series of candid, interactive discussions designed to unpack and examine what “medical value” means—and how that differs based on a stakeholder’s vantage point. While most health care leaders agree that value is some version of benefit over cost, the details get complicated quickly. Are we talking about clinical or financial benefit? Cost to whom? Benefit for whom? Over what time horizon? The answers often depend on who you ask.

Executives participate in a series of interactive-discussion-based forums

One of the most prominent and difficult tensions here is that between value for an individual and value for a population—often described as patient centricity and population health. While both are worthy goals, they are often at odds with one another, and making progress on one typically requires tradeoffs on the other. What works for a collective population may not work for the individual, and individualized care may place a higher cost burden on the population. Given the pace of advancements in technology and medical treatments, this push and pull is becoming harder to ignore.

That’s why the 2021 CIVS convened a diverse array of perspectives—across payers, providers, life sciences, patient advocacy, and other thought leaders—to examine the individual-vs-population tension in depth. The goal was not to posit that one kind of value is correct, nor to identify the right balance between the two. Instead, the aim was to better understand how various perspectives, historical forces, constraints, and roles shape decision-making in the context of this tension—and thus identify areas of disagreement and common ground.

Light Bulb Moments – and Elephants in the Room

Throughout the day, CIVS participants jotted down their “elephants in the room” and “lightbulb moments”. The elephants represented frustrations or things that often go unsaid. Lightbulbs were eureka moments—new or surprising insights, ideas, or ways of looking at an issue. The elephants and lightbulbs were gathered and posted around the walls so everyone could see what their peers were thinking and learning in real-time.

The honesty and insightfulness of the elephants and lightbulbs participants shared reflect the power of cross-industry dialogue on vexing topics like value. One elephant that caught my eye was, “Whatever is best for the patient’ sounds nice in theory, but it’s overly simplified, not always easy to assess, and not how decisions are made” which I think ties in with the lightbulb moment that “Emotions are part of decision-making, yet patient engagement and patient preferences are often an afterthought”. Another elephant I liked was “Value in healthcare involves not only clinical aspects but also sociology, politics, economics, technological issues”, tying in with the lightbulb that “Health solutions don’t have to be clinical”. Medical value doesn’t live in a vacuum (which is part of what makes these conversations so difficult). Even small decisions can have far-reaching ripple effects.

Making tradeoffs to drive “value”

One of my favorite parts of the day was the card game played in the opening keynote. The game was designed to force difficult trade-offs on very real health care scenarios. Attendees were grouped together and instructed to decide their top three “value driver cards” based on a given situation. They then had to debate and discuss which cards to swap out as new layers of information were revealed.

Attendees make value tradeoffs come to life in a scenario-based card game

One of the scenarios started like this:

An experimental treatment is being developed for a rare, life-threatening disease that affects young children, who usually die from the disease between 3 and 8 years old. There are no other treatments currently available for this condition.

What would you select as your top three value drivers here? Impact on survival? Patient financial access? Impact on quality of life? The game then took a turn as another layer was added to the scenario:

What if the price tag is $2M per year, and early evidence suggests the treatments are durable, potentially over the course of the child's life (but of course, proof won't exist for many years).

Which of the value drivers you already selected would you remove? And what would you add? What pieces of information do you wish you had?

The game progressed, adding layer after layer of complexity, and reflecting how medical evidence and our understanding of treatment impact evolves over time. One participant said “This was tough…it’s easy to have an academic conversation about how to assess value, but it becomes a lot harder when you make it real, when you think about a real child, their real parents, their caregivers…” Another said “We tried to take an objective, societal view with this exercise, but that’s rarely the way decisions are actually being made. Thinking at a societal or academic level abstracts us from the emotions inherently involved.”

Setting the stage for deeper dialogues – beyond the summit

My other favorite part of the day was the breakout sessions. Participants chose their two breakout sessions from a list of four topic areas, customizing their own unique experiences at the summit. While discussions throughout the keynote and panel were excellent, the breakout discussions were absolutely electric. The small setting allowed participants to have meaningful conversations about how the tension between individual and population value manifests across areas like clinical trials, precision diagnostics, clinical applications of AI, and everywhere care.

The 2021 Cross-Industry Value Summit focused on better understanding the tensions inherent in pursuing medical value for individuals and populations.

This conversation stemmed from Advisory Board’s inaugural value summit in 2019, which centered on better understanding what “value” means to different stakeholders. Typically, value is defined as some version of benefit divided by cost. In 2019, we unpacked that definition by looking at which components of value mattered most, to whom, and when.

The discussion exposed a key reason why a shared definition of value is so elusive: depending on your vantage point (which is driven by your industry sector, role, the patients you serve, etc.) you tend to have a different answer the question of “value for whom”—the lens of individual vs population colors how value is defined, measured, and assessed.

The individual vs population lenses are coded in the multitude of initiatives, strategic plans, and mission statements that mention “patient centricity” or “population health”. No one really pushes back that either of those aims are good, worthy, and worthwhile. Neither goal is right or wrong, but they are distinct, and they are in tension with one another because achieving one almost always involves a tradeoff on the other.

The tension is evidenced in the survey we ran leading up to this event. We asked more than 50 health care leaders across a range of industry segments about the relationship between patient centricity and population health. It turns out there’s a wide variety of opinions on whether the two are correlated. On a scale of 0 – 100 (disagree – agree), opinions averaged out at about 60, but there was no major clustering in one place or another.

This lack of consensus served as the central theme we unpacked, explored, and sought to better understand at the summit. Why is there no clear agreement? What implications does this disagreement have?

Two examples illustrating this tension are the NICU and end-of-life care: both are tremendously expensive, address very vulnerable populations (which raises societal, ethical, and moral issues), involve highly emotional states, and there’s plenty of data that the U.S. performs poorly.

Where else does the between individual- and population-level tension manifest? Summit participants identified several:

- Rare disease – treatments that put financial strain on the system for a small population

- Social determinants of health – critical for understanding value for an individual patient, but difficult to scale across entire populations

- Vaccinations for Covid – adherence to patient-centricity can directly harm public health

- Screening – how to decide who we should screen, especially in situations where there is clear benefit to the health care system in identifying patients with risk factors (e.g. BRCA) but those patients might not want to know their risks

- Allocation of resources – not just across subsets of patients, but also across health vs non-health interventions; are we consuming resources that could be better used elsewhere from a population perspective?

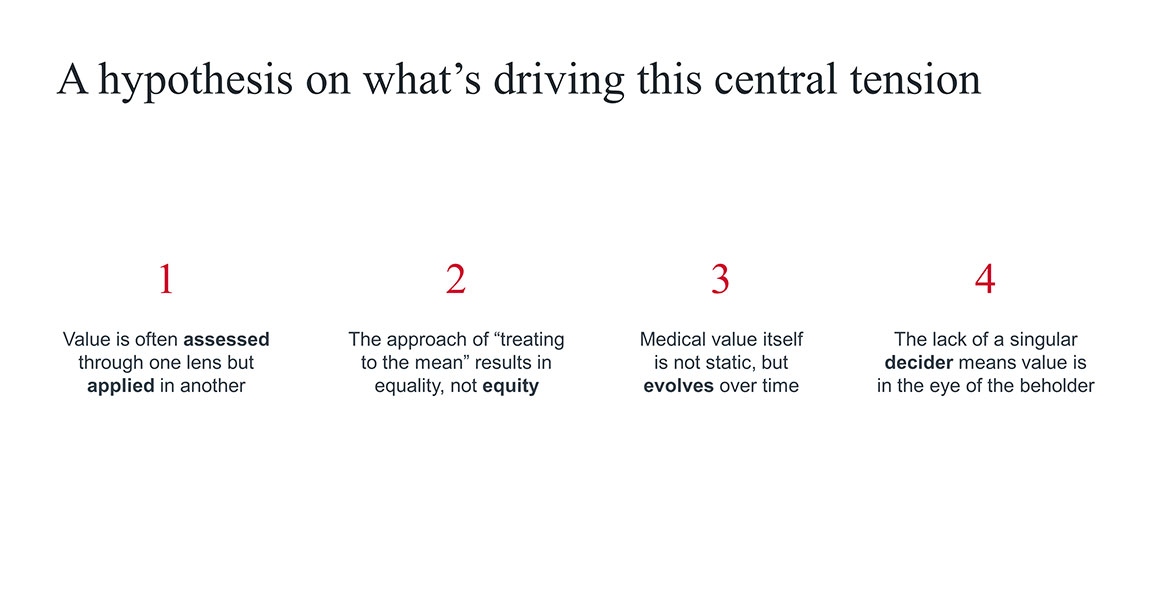

We also discussed some of the key drivers of the tension between pursuing individual- and population-level value:

- First, most value assessments (e.g., QALYs, formularies, clinical guidelines) are designed for population-level decisions, which means they can only get you so far in making value judgments for individuals. This leads to a lot of uncertainty about how valuable a given treatment is for a given patient.

- The result is that we often end up “treating to the mean” which creates equality, but not necessarily equity. Treating patients equitably by accounting for their specific SDOH needs, individual preferences, personal tolerance for risk, etc. requires scaling patient-centric care. This raises the question of whether it’s possible to be meaningfully patient-centric (and therefore equitable) across entire populations. What would that require?

- We tend to think about value as static, but it can evolve over time: medical evidence evolves over time, the patients you treat evolve over time (e.g., via off-label use or label expansion) and the care delivery system itself evolves over time (e.g., site of care shift, new kinds of support services, telehealth) – all of which have implications for value.

- Lastly, the US does not have a singular “decider” writing all the rules about what’s valuable. Instead, deciders are scattered across the industry—in frontline clinicians, in clinical societies and guideline developers, in payers and purchasers. Because those entities operate under their own incentive structures, in their own markets, with their own set of patients, and their own set of competitors and capabilities, “value” is going to mean something different to each of them.

Today’s value assessments are largely designed to inform population health decisions, not individual patient decisions. But the impending influx of high-cost, personalized, and potentially curative therapies means stakeholders must rethink how they assess medical value—and how that differs between traditional vs next-generation therapies. Next-gen therapies create new challenges not only for value assessment, but also for what data and endpoints capture value, and who should be responsible for achieving and monitoring outcomes.

In this session, leaders from different parts of the health care industry shared how they define, measure, and drive medical value in the context of next-generation therapies, and what implications this has for individual- vs population-level understandings of value.

The featured panelists included:

- Natasha Mayfield, PMP, Chief Product & Engagement Officer, Optum Frontier Therapies

- Sarah K. Emond, MPP, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, ICER

- Joe Maki, Pharm.D., M.S., Vice President, Pharmacy, Novant Health

- Moderated by: Allison Cuff Shimooka, VP of Product and Strategy, Optum Life Sciences

Key Insight: Health care leaders must expand their definition of next-gen therapies to include treatments that change how the health care system operates

To date, most health care stakeholders define “next-generation” by whether a therapeutic or intervention is curative or durable; high-cost; a cell or gene therapy; and/or indicated to treat rare disease. But the term next-generation should be much broader than that.

Panelists discussed how next-generation therapies should include treatments that change how the health care system—and especially providers—operationalize care delivery. Some next-gen therapies are delivered via new routes of administration, are used by clinical specialties that don’t traditionally manage high-cost or infusion-based treatments, or require a higher level of multi-specialty collaboration. Panelists mentioned Aduhelm for Alzheimer's, and Tepezza, the first infusion-based drug on the market to treat thyroid eye disease, as examples. Both therapies require providers to operate in new ways. For example, ophthalmologists have rarely had to administer infusion-based drugs until the launch of Tepezza.

Key Insight: Meaningfully assessing the value of next-gen therapies requires broadening our value frameworks in two ways: expanding the set of value drivers considered, and extending time horizon under which value is measured

Many payers, providers, and value assessment organizations have not shifted their mindset about what constitutes value for next-generation therapies. Many still view next-gen treatments through the same framework used for traditional small-molecule drugs: strictly evaluating safety and efficacy over a short time horizon (typically 1-2 years) based on limited data from a pivotal randomized controlled trial (RCT).

However, for many curative or durable therapies, safety and efficacy can only be established after a long period of time, which means value cannot be assessed in the short-term. As result, stakeholders must shift from looking at one-time costs and immediate clinical outcomes to a broader, longer-term set of value drivers. This includes longitudinal outcomes, the opportunity cost of not treating a patient, the overall impact on total cost of care, and patient preferences or quality of life. It can also include new-in-kind value driver For example, stakeholders are starting to consider novelty as a value driver because by making an untreatable condition treatable, there can be beneficial ripple effects in terms of better screening, better diagnosis, and better understanding of the disease etiology.

Key Insight: Evidence generators (e.g. life sciences, providers) must broaden the data sources and endpoints used to establish the value of next-gen therapies, but whether regulators and decision-makers accept this data remains in flux

Panelists discussed how the data and endpoints captured in clinical trials are not the same as those needed to assess value in the real world. To fully assess the value of next-gen therapies, stakeholders need to understand the impact on long-term outcomes and value drivers like quality of life. Capturing those metrics requires leveraging a variety of nontraditional real-world data sources – like data from wearable devices or patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

However, whether FDA and other stakeholders accept this data as evidence of value remains to be determined. Many stakeholders believe PROs or other emerging data sources have either too much or too little granularity, are “squishy,” and are not objective. For example, one panelist noted how it’s difficult to evaluate Aduhelm because “it is difficult to maintain objectivity when endpoints like quality of life and cognitive impairment are inherently subjective.”

Key Insight: Patient-defined value drivers (e.g. quality of life, experience) will be critical to measuring the value of next-gen therapies, but there’s still a long way to go in capturing outcomes that matter to patients

During the session, panelists noted how the FDA’s work on patient-focused drug development has encouraged manufacturers to recognize the benefit of capturing patient-centered outcomes. For example, life sciences companies and evidence generators that identify and measure quality-of-life metrics can “completely transform” their ability to prove their medicines’ value. Some can even justify higher price points based on this data.

However, the metrics that payers, providers, and manufacturers collect are not always aligned with what patients value. Additionally, patients often have their own definitions of terms like functional improvement or quality of life, which can impede shared decision-making between patients and their providers.

As next-gen therapies continue to enter the market, patients will be followed for longer time horizons, and information about their experiences will play a crucial role in value assessments. Organizations that don’t start collecting this data risk falling behind, even before product launch.

Key Insight: Data collection infrastructure must evolve to enable long-term evidence generation, and providers must be actively incentivized to record this data

Today, most payers and providers do not actively capture longitudinal data about the impact of next-gen therapies. One primary reason is the lack of infrastructure or incentives to capture the data in electronic health records. As one panelist noted, “As much as we want to use new-in-kind data for our analyses, we don’t have the data because there is no way to capture it longitudinally in our current medical record ecosystem, and it’s not a requirement.”

Additionally, many hospital systems, centers of excellence, and independent physician groups struggle to identify who is (or should be) responsible for capturing and tracking outcomes data longitudinally. This challenge is made more complex as physicians are already burnt out and not reimbursed for the additional tasks of data collection. Moving forward, stakeholders must identify practical ways to aggregate data and incentivize its collection.

Key Insight: To advance the use of next-gen therapies, payers, providers, and value assessment organizations must address the tension between population health and patient centricity—and recognize that definitions and assessments of value will evolve

During the session, panelists discussed how providers and payers have struggled to reconcile the tension between population-level analysis and decision-making for individual patients for next-gen therapies. However, some organizations are taking active steps to grapple with this challenge head-on. For example, Novant Health System is evolving its P&T committee to look at the population health impact of a therapy, rather than focusing on individual patient impact, and leveraging ICER reports to help determine population value. It is also starting to evaluate pharmacoeconomics from a broader value and ethical framework.

Moving forward, payers, providers, and value assessment organizations must recognize that value will evolve over time, and that our collective understanding of value will be driven by the data and evidence we measure. Manufacturers must also continue to develop evidence to inform value assessments over time.

By Solomon Banjo

Imagine you could redesign the clinical trial enterprise from the ground up. What would you change? Which key stakeholders would play a role, and when? What overarching purpose would you embed at its core? This workshop explored the ways in which the current clinical trials model struggles to meet the ecosystem’s rapidly evolving evidence needs. During the session, we theorized what it might take to recreate a clinical trials enterprise that fulfills both clinical and commercial goals.

Q: What did your session focus on?

A: Our workshop focused on understanding how the clinical trials enterprise may adapt to a rapidly evolving health care ecosystem as the industry focuses on reducing total cost of care, elevating the patient voice, combatting clinician burnout, and promoting health equity. Through a scenario planning exercise envisioning how clinical trials may adapt to these priorities, we generated interesting insights on why clinical trials struggle to inform clinical decision-making and how the ecosystem can promote a clinical trial model that better supports clinical decisions.

Q: What was the biggest takeaway from the discussion?

A: Our discussion exposed the degree to which inertia in evolving clinical trials is due to the decentralization of patients, which prevents coordinated action in support of more patient-centric trial endpoints and design. This inertia is furthered by the fact that payers might seek to maintain traditional trial endpoints in order to understand comparative effectiveness and make value-based formulary decisions—even when doing so prevents sponsors and investigators from studying endpoints that patients and clinicians need. We ultimately recognized that while we should work to dismantle legacy barriers to adapting clinical trials to fulfill clinical needs, evidence should be fit-for-purpose and does not have to be RCT-driven in all cases. Real-world evidence studies, for example, can support as well.

Q: What was surprising to you personally?

A: We were surprised by how much our conversation centered around managing the interpretation of medical evidence. Covid-19 and the recent approval of Aduhelm increased public focus on understanding and using medical evidence and, according to our workshop participants, have exposed a need for better education patients how to properly analyze and interpret evidence.

By Megan Director and Gina Lohr

Site of care shifts are helping make patient care more accessible, convenient, and low-cost. But the lack of an ecosystem-wide strategy for the shift to “everywhere care” could lead to missed opportunities or unintended consequences. This session explored how value is created—and diminished—as a wide range of outpatient, virtual, and home-based care solutions fragment care delivery across many sites, “owners,” and touchpoints.

Q: What did your session focus on?

A: Our session focused on deconstructing the ways in which the ecosystem may be missing opportunities—or causing unintended consequences—as it shifts to an “everywhere care” model defined by many care sites, owners, and touchpoints. Using a patient journey mapping exercise, we explored the ways in which patients may benefit from, and are harmed by, this new model. We then brainstormed ways in which the industry can tackle the challenges we identified in the exercise.

Q: What was the biggest takeaway from the discussion?

A: In the emerging world of everywhere care, patients need an advocate or “quarterback” that can help them navigate an increasingly complex and fragmented care delivery system. Yet if we leave that quarterbacking role to individuals and their caregivers, we risk exacerbating disparities in access and outcomes by disadvantaging patients who haven’t been given the resources or capacity needed to play this quarterback role. As a result, we must design payment models and an infrastructure that will enable all patients to interact with the health care system at the right time and in the right location.

Q: What was surprising to you personally?

A: We were surprised to learn the degree to which the shift to everywhere care creates friction not only for patients, but also for clinicians, who often struggle to attain the data they need as a result of care fragmentation and its negative impact on data sharing. It became clear that our industry must create greater continuity of care across providers in order to prevent patients from falling through the cracks.

By John League

Artificial intelligence could revolutionize health care by helping with everything from predicting the onset of clinical conditions, to improving surgeon performance, to hastening discovery of novel treatments. But there is real concern that the increasing adoption of AI could provide unequal value that exacerbates existing disparities. This workshop examined what it will take—and who is responsible—to ensure that we equitably deliver value on AI solutions that aim to improve patient care and treatment.

Q: What did your session focus on?

A: AI has few use cases in health care today compared to other industries. However, even when we eventually overcome the operational barriers that currently limit the extent to which AI works in health care, a host of tensions and ripple effects still prevent us from ensuring AI provides value in health care. In this session, attendees debated the key tensions of AI’s value at an individual vs. population level, the balance of the human and the machine in decision-making, and potential ripple effects that a successful AI algorithm may generate.

Q: What was the biggest takeaway from the discussion?

A: Adding effective AI at the point of clinical care won’t only change the accuracy, speed, and cost of diagnoses. It also raises questions like, “What is medical decision-making?” because there will likely be impacts on the role of the clinician and how we pay for care depending on whether a decision is made by a clinician or an algorithm.

Q: What was surprising to you personally?

A: One surprising revelation was that getting people to trust any organization (health care, Big Tech, etc.) with their health data is not going to get easier over time. Digital natives like Gen Z are keenly aware of their data footprint, and they aren’t likely to opt-in to data-sharing as a default just because they can’t remember a world without smartphones.

By Deirdre Saulet

Precision medicine is often touted as the future of medical treatment, but when assessing its value through a cost-effectiveness lens, most precision diagnostic tools don't seem financially viable. Does that mean they're not valuable? Or is cost-effectiveness the wrong metric here? This workshop will unpack how we apply frameworks for "value" in the context of precision diagnostics (PDx), how our understanding of "population" changes as a result, and what role industry stakeholders can play in advancing precision medicine.

Q: What did your session focus on?

A: Health care is shifting from a largely trial-and-error approach to treatment, toward a more individualized and precise approach enabled by precision diagnostics. While there's no shortage of new innovations in PDx, an ongoing challenge is the industry's reliance on population level cost-effectiveness as the primary framework for assessing value. Providers and payers are hesitant to invest in PDx without proof of cost-effectiveness, but cost-effectiveness is difficult to prove without investment and longitudinal data. This session focused on how the primary value framework should be redefined so the industry can more fully leverage PDx for patient care.

Q: What was the biggest takeaway from the discussion?

A: It is far easier to view patients as cells and bodies than it is to acknowledge that patients are complex beings, sometimes irrational, with a range of interests, expectations, and wishes for their lives. The ecosystem has traditionally excluded patient voice when determining the value of precision diagnostics despite the many moral and personal quandaries it can raise. Moving forward and advancing the use of precision diagnostics will require various stakeholders—especially patients—coming together to discuss misaligned perspectives and decide who (and how many who’s) value should be centered around.

Q: What was surprising to you personally?

A: Especially in the last year, the topic of health equity has been top-of-mind, with many stakeholders making it a priority. There is a huge potential for precision diagnostics to worsen health equity and widen the gaps between the haves and the have-nots. Precision diagnostics tests often carry very high price tags, and so far, the health care ecosystem has not come to consensus on how to carefully move forward (and who should be agents for change) to advance the adoption of PDx without exacerbating inequity.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.