Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutDiagnostic discordance—when a patient receives different diagnoses after being transferred—occurs in roughly 85% of hospital transfers, according to a study in the Journal of Geriatric Internal Medicine.

Two ways to identify clinical variation—and improve outcomes

The problem of diagnostic discordance

According to 2015 data from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, about one-in-20 hospital patients get transferred. The Star Tribune reports that there are several reasons why patients might be transferred. For instance, a heart attack patient who presented at a community hospital might need surgery at a cardiac center, or a person with a mental health condition might present at the emergency department and be transferred to a psychiatric bed in a different facility.

Previous research has shown that patients who are transferred have longer hospital stays, experience more medical errors, and have an increased risk of death. But the Tribune reports that it is unclear how much of the increased risk is due to diagnostic discordance, as transferred patients tend to have more complicated medical records, which increase the risk for discrepancies. Researchers at University of Minnesota (UM) Medical School conducted the latest study to determine how frequently diagnostic discordance occurs.

Study findings

For the study, researchers led by Michael Usher, an assistant professor in general and preventive medicine at UM, reviewed billing records for over 180,000 transfers among patients with incurable diagnoses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that should always be included in medical records.

The researchers found discrepancies in diagnoses in 85% of the examined transfers. However, according to the researchers, patient transfers between hospitals using the same data-sharing mechanisms were associated with a lower rate of information loss and mortality.

The Tribune reports that some variation in patient diagnoses is understandable, as patients presenting with pain at one hospital might be diagnosed for the underlying condition at another, while in other cases, a patient's health status might improve by the time he or she reaches the new hospital.

But Usher said his study showed instances in which diagnoses for patients with incurable diseases were missing. Usher said it was not "the diagnosis [that] was being lost. It was the information being lost in the transfer from one hospital to another."

For example, Usher cited his own experience as a hospitalist, recalling one case in which a patient who was accepted for a heart procedure experienced a cardiac arrest that could have been prevented if the previous hospital forwarded information about the patient's severe kidney failure.

"There's frequent communication breakdowns, and that results in real-world problems for patients, including mortality," Usher said.

How UM Medical Center is trying to resolve diagnostic discordance

According to the Tribune, diagnostic discordance is a "little-discussed" problem, but there are ways hospitals can address it.

The UM Medical Center is testing a pilot program that immediately transfers patient information when the patient is transferred. Researchers also are assessing whether data is lost when patients are transferred between different types of facilities—from a hospital to a nursing home, for instance—and how a patient's insurance status might or might not affect data transfer.

EHR interoperability also is key, the Tribune reports. While most hospitals in Minnesota have EHRs, interoperability between hospitals is inconsistent. According to survey data from the Minnesota Department of Health, 63% of hospitals have routine access to EHRs from outside hospitals or clinics.

According to Jennifer Fritz, the health IT director for the department, that is a problem, since many patients use doctors from different organizations. "We've made really good progress in the state in the adoption of that technology," she said, adding, "But the interoperability of that technology? We're still working on that" (Olson, Star Tribune, 7/28; UM Medical School release, 7/16).

One key to improving your hospital's quality: Identify clinical variation

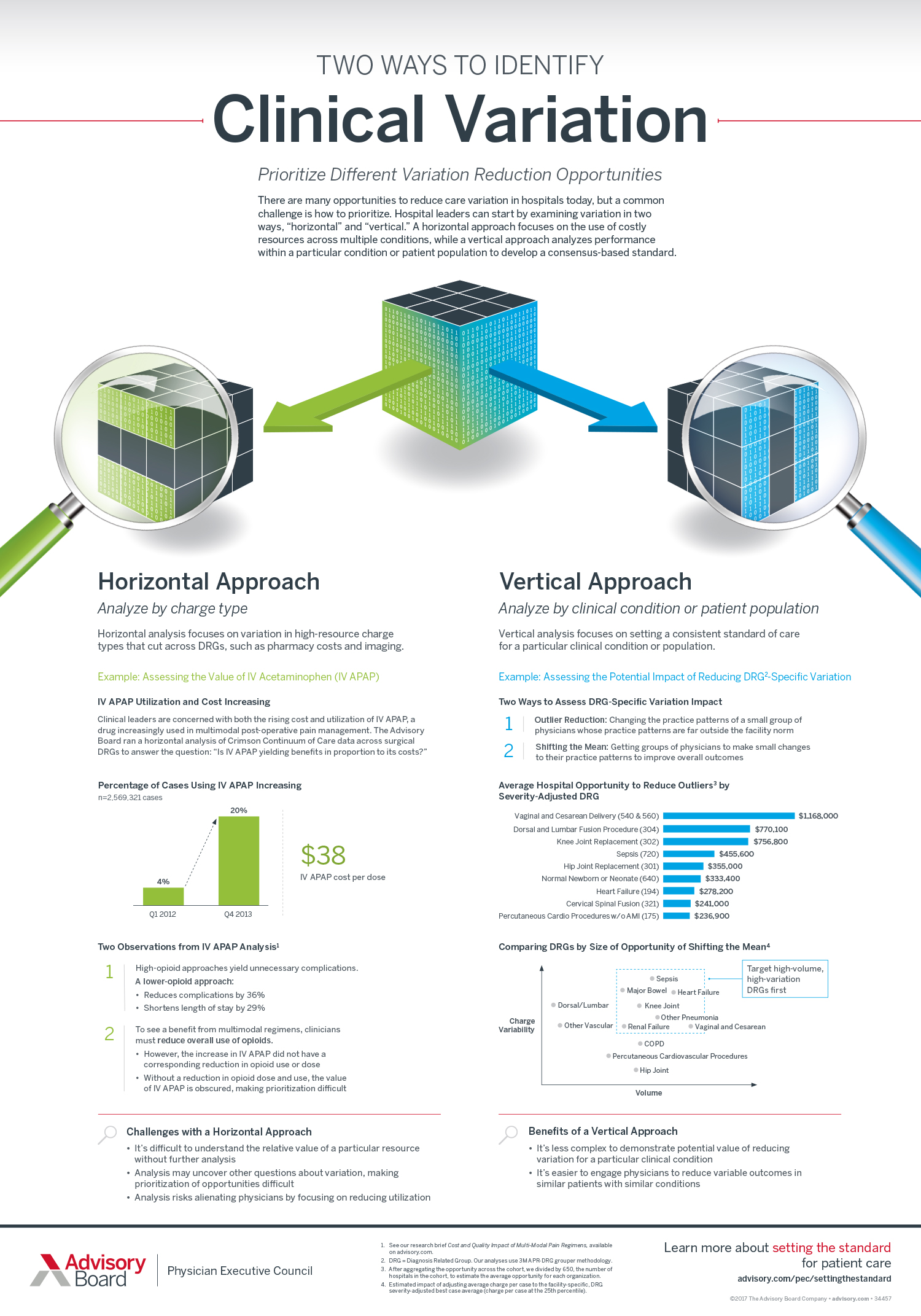

There are many opportunities to reduce care variation in hospitals today—but how should you prioritize those opportunities?

You should start by examining variation in two ways: "horizontal" and "vertical." A horizontal approach focuses on the use of costly resources across multiple conditions, while a vertical approach analyzes performance within a particular condition or patient population to develop a consensus-based standard.

Our infographic gives an example of each approach and explains the challenges of a horizontal approach versus the benefits of a vertical one.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.