Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutTelehealth is poised to have a dramatic, industry-wide impact on care delivery. In particular, video visits and remote monitoring could transform how we think about clinical guidelines, how we track outcomes, how we manage patient hand-offs, and how we determine which care happens in which settings.

But today—especially with a Covid-driven uptick in adoption—most health care leaders are focused on addressing near-term challenges, like adapting clinician workflows, predicting volume shifts, and planning for changes to reimbursement. To ensure telehealth adoption is sustained appropriately in the long-term, stakeholders must also plan for the second order impacts and consequences that will emerge as telehealth use expands.

Below are five “ripple effects” health care leaders should be aware of—and take action on—as they anticipate the impact of telehealth adoption in the future.

Click each ripple effect for more detail.

1. Telehealth adoption will stagnate without standards for quality and appropriateness, but those standards can’t be determined by individual organizations.

To sustain adoption in the future, there must be consensus about when it’s appropriate to provide telehealth. Currently, there is little consensus outside of the “bread-and-butter” of telehealth, which is minor urgent care. But that consensus is largely about whether it’s safe to provide certain types of care virtually, not whether telehealth is the most appropriate modality.

A lack of consensus about what constitutes high-quality telehealth and when telehealth is an appropriate option is a key barrier to adoption today: it contributes to skepticism among clinicians that telehealth is bad medicine; to payers not trusting that local providers can provide good telehealth (and often opting for vendor-based solutions); to local providers not trusting telehealth vendors to provide good care; and to payer and provider concerns that more telehealth equates to unnecessary utilization. Ultimately, this means we can’t agree about how telehealth should be reimbursed.

Although very few organizations have created clinical guidelines or quality metrics for telehealth today, we can expect more organizations to do so as telehealth becomes more widely adopted. But this is unlikely to solve the trust problem because those guidelines and metrics will almost certainly vary by organization.

In order to overcome these concerns, a cross-section of industry stakeholders must come together to establish guidelines for quality and appropriate use. In particular, this will require collaboration among telehealth-focused professional societies (like American Telemedicine Association) and clinically focused societies (like American College of Cardiology). But all stakeholders, including technology firms, providers, payers, and individual clinicians should think about their role in shaping the frameworks and standards by which telehealth will evolve.

2. The question of reimbursement parity will become irrelevant; instead, telehealth’s value will be determined by its impact on specific patient needs.

One of the biggest barriers to telehealth adoption today is reimbursement. In general, providers hesitate to invest in telehealth because reimbursement is uncertain or too low, and payers hesitate to reimburse because the value of telehealth is unclear.

In large part, this barrier is tied to the mindset that telehealth is an end in and of itself. In many cases, health care leaders think of telehealth as a replacement for in-person care, rather than a tool to achieve specific goals. We frequently hear C-suite executives at large provider organizations ask, “Should we be doing RPM?” while their health plan counterparts ask, “How should we cover virtual visits?” When the goal is to replace in-person care with telehealth, we naturally revert to benchmarking its value against in-person interactions. And that’s where we get stuck on the question of whether reimbursement parity is justified.

To actually quantify the value of telehealth, stakeholders must assess it in the context of specific use cases. For example, is the goal to improve pregnancy outcomes in rural areas? Or to more effectively manage patients with chronic disease? The metrics payers and other decision-makers use to determine value will be (and should be) different depending on the purpose for which telehealth is employed.

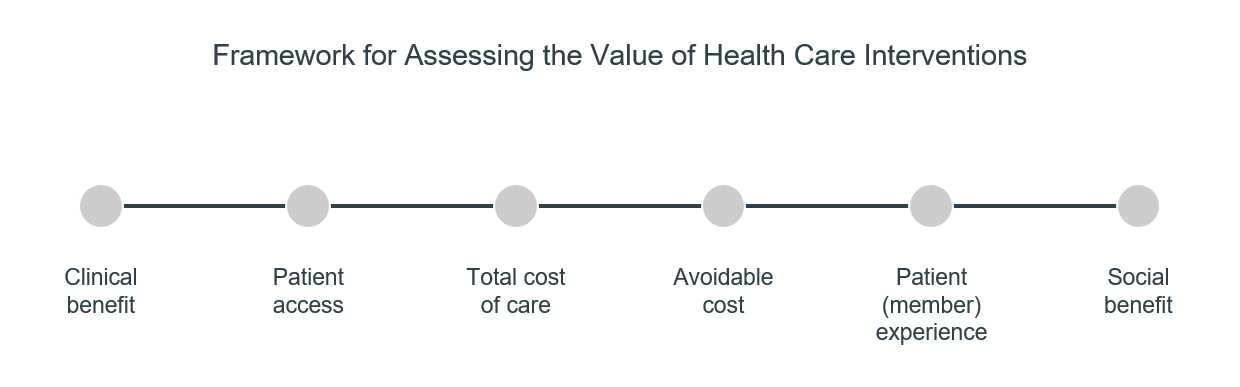

Ultimately, assessing the value of telehealth requires expanding how we think about value itself. If value is defined simply as benefit over cost, we’re left wondering what counts as benefit, and what counts as cost. For example, does benefit only include clinical outcomes? How should we account for peace of mind, or patient convenience? Should we distinguish between cost to the patient and cost to the system? Value is inherently multifaceted, multi-stakeholder, and use case dependent—and is made up of several distinct drivers.

3. Data sharing and interoperability will be ‘table stakes’ for telehealth to become fully, appropriately integrated into care delivery.

Aside from payment parity, this is the number one barrier cited by leaders we speak with: we don’t have the data we need from our partners, or if we do, it doesn’t integrate.

This barrier has efficiency and effectiveness implications at the point of care. For example, clinicians may have to manually duplicate EHR information, or may not have a patient’s medical record available in time for a virtual visit. The seamless portability of individual patients’ data is a basic prerequisite for telehealth to have any kind of meaningful, scaled impact on care delivery.

But there are broader implications for the industry as a whole, too. Without the right data—shared and aggregated across the many platforms, tools, and institutions involved in patient care—we cannot answer the key questions holding telehealth back today: Is telehealth valuable? What’s the ROI? Is this the right care option for my patient? Lots of stakeholders, especially life science firms, technology vendors, policy makers, and clinical guideline developers all have a vested interest in determining when telehealth is most appropriate, which requires creating high-quality data sets about telehealth use.

There are several ways stakeholders can take action to advance data sharing and interoperability for telehealth. First, individual organizations must determine what kind of data they would need to make key decisions. In our conversations with health care leaders, it is clear that most organizations don’t know what specific endpoints they would need to make coverage decisions, to determine value, to measure quality, or to assess the impact of telehealth on strategic goals. Stakeholders must start by deciding and articulating what kind of data they need (and when), so they can prioritize efforts and focus their conversations.

Health care leaders must also work toward developing a common language (and eventually a broader, more specific set of codes) for telehealth services. Today, some organizations use terms like telehealth and telemedicine to describe different services, while others use them interchangeably. This not only complicates billing and reimbursement, it also creates challenges for data aggregation since individual data points are not standardized.

Finally, leaders should determine how to support the development of data sharing and interoperability standards. Since adoption of technology and HIE is historically driven by regulatory incentives, leaders should get involved in ongoing multi-stakeholder initiatives designed to inform those regulations. For example, the Sequoia Project brings together payers, providers, technology companies, and other stakeholders to develop shared frameworks for data exchange.

4. Technology innovation centered on consumer preference will widen health disparities unless leaders take deliberate steps to accommodate underserved patients.

It’s no secret that telehealth won’t solve access-related health disparities. Regardless of how widely telehealth is used, structural problems will remain, including a lack of reliable broadband, access to insurance coverage, and training among clinicians to care for marginalized patients. Without addressing these structural barriers, the increased adoption of telehealth actually exacerbates disparities.

This risk is even more pronounced when we look at telehealth innovation. Take mental health care for example, where patient demand far outpaces clinician supply. An entirely new market emerged in response to this gap, featuring about 1500 unique mental health apps like Sanvello, Calm, and Talkspace. While these innovations certainly chip away at the supply-and-demand problem, about 1 in 5 US adults doesn’t own a smartphone, meaning these apps are inaccessible to a large portion of patients. If funding for telehealth innovation is centered on consumer demand, and most demand comes from relatively wealthy populations, we risk categorically leaving behind large groups of vulnerable patients.

A cross-section of industry stakeholders—including technology vendors, providers, legislators, and patient groups—must work together to ensure telehealth programs are designed with vulnerable populations in mind. But this means addressing more than just broadband and smartphone access. Telehealth programs and technologies should support patients with audio-visual impairments. They should include patient education and digital literacy campaigns. And finally, telehealth programs must address trust barriers between marginalized communities and the health care system—especially since trust is more difficult to establish when communicating through a phone or computer.

5. Telehealth could potentially worsen care fragmentation, but not in the way we typically think.

In theory, telehealth should improve care continuity. By offering virtual visits, providers make it more convenient for patients to get follow-up care from their own doctor. And through RPM, clinicians and patients have access to steady streams of data, creating a more consistent and continuous feedback loop of information.

But a major concern—particularly with regard to large national telehealth vendors—is that telehealth creates fragmentation that could hurt patient outcomes. For example, if an elderly patient who presents with joint pain is given ibuprofen, but subsequently shows signs of kidney failure, she would immediately be taken off ibuprofen. If, however, she later sees a different provider via telehealth and mentions her joint pain, she is very likely to be given ibuprofen again, especially if she didn’t understand or remember the risk it posed. This type of potentially dangerous redundancy is not uncommon when a patient’s care is fragmented. And some leaders, especially provider leaders, worry that telehealth increases the likelihood of these occurrences.

So how can we determine whether telehealth is improving or worsening care continuity? Distinguishing the true versus perceived impact of telehealth requires acknowledging that care continuity is not one thing. There are at least three distinct components of care continuity, all of which could theoretically change with more telehealth.

- Continuity of information has to do with seamless transfer of the medical record and other relevant clinical and non-clinical data from one point of care to the next. Continuity of information is important for all patients but is especially critical for complex patients with more than one condition, where the risk of care redundancies or adverse events (e.g. from a drug interaction) is higher. Telehealth could make continuity of information worse in the near term, but only if more telehealth means patients receive care from more organizations than they did before, and the patient’s data remains siloed within those organizations.

- Continuity of relationship has to do with the individual, human relationship built between a clinician and a patient. This type of continuity may be more or less important depending on patient preference but is especially critical when personal rapport and consistency can impact patient outcomes (e.g. in behavioral health care, where the close patient-provider relationship can significantly shape a patient’s trajectory). It is unlikely that telehealth will worsen this kind of continuity, because if a patient values their relationship with a particular provider, they are unlikely to opt into a telehealth model that undermines that relationship.

- Continuity of service has to do with the chain of interactions and services that make up a patient’s care journey. This includes specialist referrals, orders for diagnostic tests or labs, new prescriptions, and follow-up visits. Telehealth will almost certainly impact the patient journey, but how telehealth affects continuity of service is not clear. For example, if an in-person primary care visit leads to a blood test, the patient can usually receive that test in the same building. Or if it results in a new prescription, the patient may be able to pick it up in the provider’s in-house pharmacy. However, if the primary care visit were to occur virtually, any tests or prescriptions could require the patient travel somewhere in person, which could feel like a point of fragmentation in their care journey. At the same time, other kinds of virtual visits like post-surgical follow-up could improve continuity of service by removing access barriers. So far, it’s not clear how often telehealth visits lead to downstream services, and to what extent the patient journey becomes fragmented as a result.

It is difficult to predict with certainty how telehealth will impact care continuity, because continuity can mean different things in different contexts. But thinking about telehealth as a tool to enable continuity raises a series of interesting questions:

- How will the role of the PCP evolve? To what extent will the PCP’s role be driven by consumer preference versus whatever proves to be the most clinically effective model?

- What information must be collected at the point of care and shared in order to support care continuity? What information is nice-to-have but not need-to-have?

- How should information captured by devices (including RPM devices and digital therapeutics) be shared and used to support care continuity?

What does this mean for my organization?

Telehealth presents an enormous opportunity to change patient care for the better. But in the absence of thoughtful planning and multi-stakeholder collaboration, telehealth is just as likely to exacerbate many of the existing failures in our current delivery system. Below are the 2-3 biggest questions industry leaders should ask to ensure they are doing their part in getting telehealth right.

Payer- What data and metrics do we need to measure telehealth’s value, and from whom?

- What should we provide our members to ensure equitable access to telehealth (e.g. tablet, Apple Watch, internet access)?

- What patient information is critical to have at the point of care, and what must be captured at the point of care to support future clinical interactions?

- Which unmet patient needs is our organization well suited to address, and which needs are best addressed in partnership with telehealth vendors?

- How can we participate in defining quality and appropriateness for telehealth?

- How can we enable interoperability so the data we share is not just accessible, but actionable?

- How well does our solution account for external barriers our users may encounter (e.g. digital literacy, affordability)?

- How does telehealth impact patient hand-offs, in terms of specialist referrals and transfers to ancillary services (e.g. diagnostics, labs, imaging, pharmacy)?

- To what extent will telehealth influence market adoption of digital therapeutics and companion devices?

- How does telehealth change the types of clinicians that influence care decisions (e.g. advanced practitioners, registered nurses, pharmacists)?

- How does telehealth change which services are prioritized for co-location?

- What facility infrastructure is required to enable telehealth workflows?

- How should our talent pools change to support care via telehealth?

- What new skill sets or training do staff need in order to provide care through various telehealth modalities?

What other telehealth questions should our research team be thinking about? What other ripple effects are you planning for? Reach out to Katie Schmalkuche (SchmalkC@advisory.com) to discuss.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.