Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutI was reminded this week that, even with the epochal epidemic now gripping the nation, this is still a presidential election year.

Clearly, the new coronavirus is the biggest issue on Americans' minds—but if anything, it only makes more pertinent the long-running debate in the Democratic presidential primary about health care reform. If enacted, both Sen. Bernie Sanders' Medicare for All and former Vice President Joe Biden's public option would have major consequences for the financing and delivery of U.S. health care.

Where Sanders and Biden stand on health care policy

If you think it's too early to consider the consequences of these plans… well, you're probably right. We don't know who will win the presidency, let alone Congress. And just because a president proposes a plan doesn't mean it will become law, and even if it does, it will morph dramatically along the way (let us all remember the journey the Affordable Care Act took to become law).

Oh, and let's not forget the Supreme Court, who might have to adjudicate any major legislation. And the COVID-19 outbreak may continue to shake up the health reform conversation. And so on.

I know. I know. Speculating on any major health care legislation is way too premature.

But amid a tremendously difficult week in health care, let's allow ourselves a bit of fun with math and do so anyway.

The Sanders plan: What 'Medicare for All' would mean for health systems

Sanders' presidential prospects, while dimming, are not yet extinguished. And besides, the public option is often derided as a backdoor to single payer, so it's worth looking at what the full Monty looks like.

For today, let's limit our analysis to hospital and health system revenue. And let's start with Antares Health System, Advisory Board's astronomically named, and entirely fictitious, model health system that we've used to assess necessary targets for growth and cost control. (Longtime Advisory Board members might recall that Antares is a typical five-hospital health system, with roughly $1 billion in annual revenue and a respectable 3% operating margin. For assumptions about payer mix, revenue, costs, etc., please check out our Antares model.)

Sanders' single-payer proposal would transition Americans to a government-run plan and remove patient cost-sharing responsibilities. It's difficult to predict exactly how health care consumption would change, but it's reasonable to assume that patients would utilize more high-cost services.

Previous coverage expansions—such as the passage of Medicare in 1964 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010—did not significantly increase inpatient utilization, so we can expect increases in utilization would overwhelmingly occur in the outpatient setting. We estimate an average uptick of 13% given Antares' payer mix.

Under Sanders's Medicare for All, Antares would receive 100% of Medicare payment rates for all patients. Even after accounting for the expected increase in outpatient utilization and coverage for the uninsured, Antares's revenue is projected to decline by a rather alarming 23%, assuming current commercial rates of roughly 200% of Medicare. (These declines scale up quickly if your commercial reimbursement is substantially higher.)

How can your system stave off Antares' fate? A few options:

- Lobby for higher Medicare payment rate. A lot higher. For Antares to match its revenue under today's payment system, increases in utilization mean that Medicare payment rates would need to be about 130% of what they are today. But this would run counter to Medicare for All's goals of reducing overall costs, so such a payment increase would be highly unlikely.

- Capture as much market share as possible. The typical hospital today operates at about 60%-65% occupancy (leaving excess capacity that, as we will soon see, can be an asset during natural disasters or epidemic outbreaks). At the proposed Medicare for All rates, those occupancy rates would likely not be enough to keep many providers viable. But could those that remain stay in the black if occupancy rates look closer to full (typically thought of as 80% average occupancy)? Sort of: At 80% occupancy, Antares will regain only 16% of its missing revenue. If Antares is going to recapture the remainder, it must win many more patients in the outpatient setting. In Antares's market, it would need to increase its outpatient market share from roughly 15% to 20%.

- Drastically cut costs. Over the past decade, hospitals and health systems have proven themselves remarkably adroit at cutting expenses when conditions require it (although in recent years, margins have contracted because prices have stagnated). Medicare for All would present a very different challenge because of the sheer magnitude of the revenue drop. Providers would likely run up against state and local laws surrounding patient ratios, capital upgrades would grind to a halt, and average age of plant would likely be allowed to rise.

But as overhauls to the U.S. health care system go, Medicare for All isn't the only option.

The Biden plan: What to expect from a 'public option'

In the past several weeks, Biden has experienced a comeback few would have predicted a few months ago. He promises a health reform that is, on one level, far less radical: an alternative to traditional insurance plans, with premium rates for patients and payment for providers all set by the government. But if anything, the public option is subject to even more unknowns—not least because the Biden campaign has released few details.

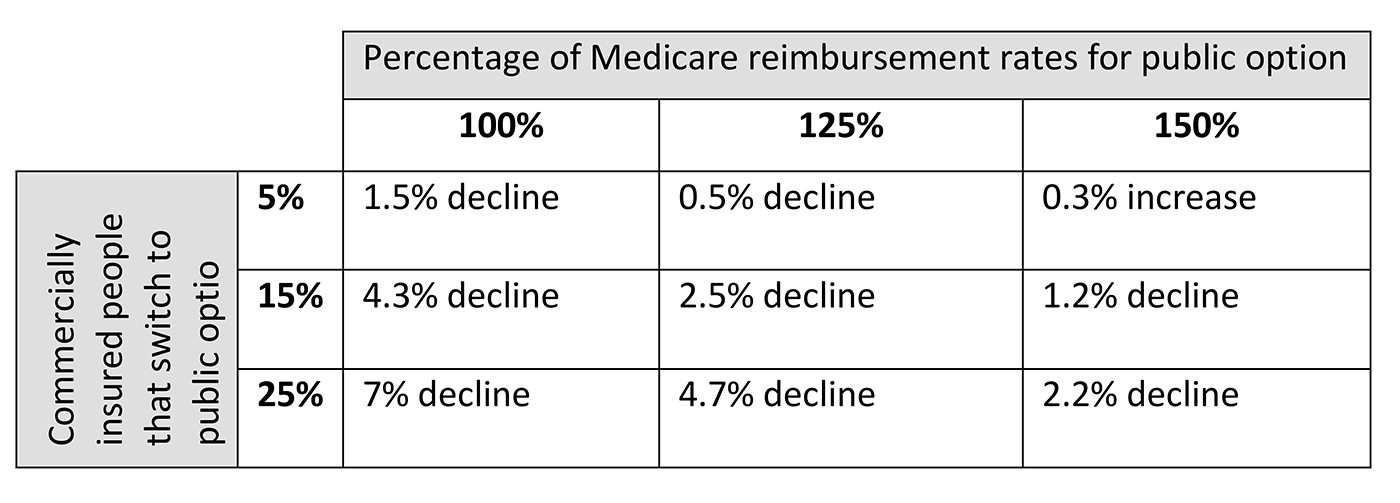

But any public option's impact will be most dependent on two factors: (1) how many people switch to the public option, and (2) the rates paid to providers, which can vary dramatically.

But both of these figures are tough to pin down. Estimates for switching behavior vary based on the how much the public option differs from traditional insurance and whether it's available outside of the individual market. And proposals for provider rates range from current Medicare levels to those approaching 150% of current Medicare rates (still well-lower than typical commercial rates).

For the purposes of this analysis, we looked at a range of scenarios for Antares. Each scenario assumes that the majority of nation's remaining uninsured partake of the public option, and that the plan is financed with patient premiums with normal cost-sharing, leading to little change in overall utilization.

If payments to providers are relatively high, premiums are likely to be higher too—and relatively few people will switch to the public option. In that scenario, the plan is net positive from the reduction of uninsured.

But if payments are relatively low, more people will switch from commercial insurance—resulting in the worst-case scenario for most hospitals and health systems (absent major government subsidies).

When we look at the impact for Antares, most scenarios are slightly to moderately negative because the modeled rates would still fall well below commercial levels.

Some major caveats here:

- Patient mix. This analysis assumes a uniform commercial population, but in reality, the impact of a public option will depend on which patients switch into the public option. For example: Do beneficiaries in the public option have high levels of chronic disease? Will they consume more procedural care?

- Payer mix. Organizations with a higher amount of government payers, such as rural and safety net hospitals, could see an overall increase in revenue. Antares has a large number of commercially insured patients, and therefore is more likely to see an overall decline in revenue when patients shift to a lower-reimbursed public option plan.

What to watch for

Although Biden and Sanders are the last major Democratic presidential candidates standing, that doesn't mean we should ignore the plans initially offered by other candidates, whose plans could still serve as the model that Congress ultimately adopts. (After all, several of the former candidates are still in Congress!)

It's notable, then, that most of the other candidates' plans didn't eliminate the private insurance system as it stands today—stopping short of true "Medicare for All." Most also stopped short of transitioning those covered by employer-sponsored coverage to a public plan. These details are often overlooked in the political conversation about health reform, but they have a huge impact on how a given proposal will impact the industry.

So what details should we look for moving forward? As the ultimate presidential nominees release more information about their proposals, here are some of the key points Advisory Board will be watching for:

Target population: Does the proposal target only the currently uninsured, or would it shift those with private insurance to public insurance? Would coverage be mandatory or optional?

Reimbursement level: At what level will payments be set? How do rates compare on an aggregate basis considering current uncompensated care cost?

Timeline for implementation: How quickly would changes be phased in?

Administrative impact: To what extent will the proposed changes result in decreased administrative costs through simplified revenue cycle operations?

Impact to utilization: Will decreased cost sharing, broader payer networks, or expansion of coverage to previously uninsured populations increase health care utilization?

Workforce impact: What will happen to the employees of private health insurance companies if patients transition to a government-run single payer? What will happen employees of hospitals that close as a result of lower reimbursement rates?

And one final question, which remains hard to answer: What impact will the COVID-19 outbreak have on the health reform conversation? Already we've seen an openness to a greater public role in financing health care, even from Republicans who've traditionally cast skepticism on public financing. If the epidemic considers for months to come, our national politics could been shaken in ways we still can't predict.

(Sorry, I know I promised you a change of pace from COVID-19.)

I hope everyone reading this is hunkering down, ready to face the potential challenge that awaits in the coming days and weeks. But as we emerge at the other end of the coronavirus outbreak, let's remember that there's still an election on—and it's likely to be the second most important health care story of the year.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.