Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutRead Advisory Board's take: 3 factors limiting the watch's potential impact

It's been several weeks since Apple announced that its next Apple Watch will feature an FDA-cleared electrocardiogram (EKG), and providers and health care experts are still debating whether the benefits of the EKG feature will outweigh the harms.

About the EKG feature

A typical EKG is conducted in a doctor's office or hospital and requires attaching electrodes to a patient's chest. But Apple's new EKG app requires only a simple press—and 30-second hold—of a button on the watch, after which it informs a user if his or her heart rhythm is normal or if her or she is experiencing atrial fibrillation. The data, which Apple said are encrypted, are then stored in the iPhone's Health app, where users can access it and create PDFs to share with their physicians.

FDA in a statement cautioned that the device is cleared only for those who are at least 22 years old and have not been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, a heart condition that can increase the risk of stroke and affects an estimated 2.7 million Americans. The agency also cautioned that the device is cleared only to detect irregular heart rhythms and is not guaranteed to sense every instance in which an individual's heartbeats are abnormal.

One doctor seeks to temper expectations

Aaron Carroll, a professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, in the New York Times' "The Upshot" notes that some observers have hailed the EKG feature as "a great leap forward"—but Carroll says he has two major concerns about the new device.

The first is that it could lead to an increase of misdiagnoses. He explains, "A false negative might leave someone who needs medical help with a mistaken sense of assurance." But the bigger problem, according to Carroll, is false positives—when the watch wrongly informs someone that he or she is suffering from atrial fibrillation. Follow-up treatment of such individuals will "cost us time and money, as well as cause emotional distress."

This is likely to be a significant problem, Carroll writes: "Before granting clearance, [FDA] reviewed data collected by the Stanford Heart study for 266 people who" received a notification that their heartbeat was irregular. "Most of the notifications were wrong," Carroll adds.

The other issue, Carroll writes, is "[t]he people most in need of it, those who might benefit from tests and distance monitoring, are the least likely to get it." That's because people who buy the Apple Watch "will most likely be younger, healthier, wealthier and more plugged into the health care system—and less likely to remain undiagnosed," he explains.

Carroll argued, "If we truly believed this was a medical test beneficial to the general population, insurance should pay for it. No one is suggesting that should happen." Carroll notes the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reviewed a meta-analysis of 16 studies and determined EKG screenings should not be performed on asymptomatic patients at low risk for cardiovascular diseases.

Carroll acknowledged that he himself is an Apple Watch owner. But he writes, "I'm under no illusion they will help me lose weight or exercise more or improve my heart health. I own one because I want it, not because I need it." He adds, "That's the same criterion you should use, too."

But two providers urge doctors not to 'dismiss' the new feature

On the other hand, in a recent Harvard Business Review article, Christopher Worsham, a critical care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and Anupam Jena, an internist at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, write that while concerns about unnecessary tests "are valid, doctors shouldn't be too quick to dismiss the new feature."

In fact, they argue the device could prove valuable to physicians and aid treatment. For example, Worsham and Jena write, "In theory, for patients with chest pain, emergency physicians could pull up an ECG taken by a patient before that patient arrived to the hospital, helping the physician make a better diagnosis and expediting treatment, perhaps by identifying specific heart rhythms that are seen in conditions like heart attacks."

In addition, they note that the Apple Watch user base, which was estimated at 18 million in 2017, "could generate unprecedented data."

Worsham and Jena note that the data could be aggregated across watch users, linked to clinical information, and analyzed to better understand how often abnormalities of the heart are the root cause of patient morbidity and mortality." They write, "[I]f ECG data and particular ECG abnormalities can be linked to adverse health outcomes, it's possible that algorithms to detect these abnormal rhythms may be developed."

On the individual patient level, they note that the data could shed more light on patients who suffer "sudden cardiac death." They explain, "If patients had recorded an ECG before they died, medical examiners could also review the data and gain more insight into the cause of death, including … whether it was a heritable condition." They continued, "Researchers could also use ECGs collected from Apple Watches to study changes in the heart's electrical activity in large numbers of patients who have other non-cardiac diseases, who are taking specific medications, who live in certain areas, who eat certain diets, and so on—the possibilities are difficult to predict."

Worsham and Jena concluded, "As doctors reasonably question whether these technologies will lead to unnecessary doctor's visits, testing, and patient anxiety, it's important to recognize the opportunities and to push for the creation and sharing of the unique data that they generate" (Worsham/Jena, Harvard Business Review, 10/5; Carroll, "The Upshot," New York Times, 10/8).

Advisory Board's take

Megan Tooley, Practice Manager, Cardiovascular Roundtable

It's great to see that the medical community is seeking new ways to leverage technology to empower and engage patients—especially in the cardiovascular space where early engagement is essential to improving long-term outcomes. However, many cardiovascular specialists remain skeptical about the true potential of the watch in this space.

As I see it, there are three main factors limiting the watch's potential impact:

- Arrhythmias are very complex and patient-specific. While Apple's algorithms certainly may be able to detect cardiac abnormalities, diagnoses are ultimately influenced by a number of patient-specific factors. Therefore, while this watch might be able to start a conversation, patients ultimately need to work with their doctors to determine what their baseline is and what requires clinical attention.

- Owners of Apple watches are likely younger and healthier—not the high-risk population that would most benefit. People who are buying the latest technology, and who are able to spend several hundred dollars on the watch, are likely not those at the highest risk for heart problems. They are also more likely to be plugged into the health care system already, which makes it less likely that the watch will be able to pick up on many undetected conditions.

- False positives could lead to more visits by the "worried well." As the story above mentions, the high potential for false positives could lead many healthy people to think they have a problem—and schedule an unnecessary visit, or visit their ED, as a result. This would be bad for cardiologists, who likely already have packed patient schedules; patients, who have to pay for expensive avoidable visits and testing; and health plans, who could see a rise in spending.

As a result, this use of the watch may well provide a very high-profile example of a technology that has an admirable goal of improving wellness, but which may inadvertently lead to unnecessary care and costs to the system.

Yet that doesn't mean that providers shouldn't discount all of the new market trends and innovations in the cardiovascular space. To get a snapshot of the major market trends and priorities CV leaders should know, download out research briefing on How to Build Your No-Regrets CV Strategy.

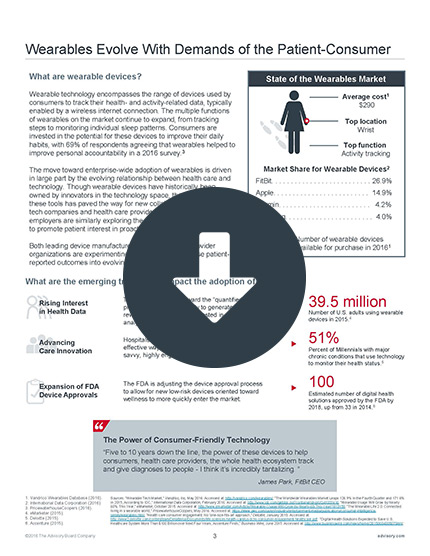

To learn more about how wearbles are changing clinical practice, and what your organization should know about how to manage the data they produce, be sure to download my colleagues' report on Incorporating Wearables Data into Clinical Practice.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.