Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutEditor's note: This popular story from the Daily Briefing's archives was republished on May 16, 2023.

At some point, a person grappling with a life-threatening illness "comprehends, on a gut level, that death is close"—a realization that in many ways acts as a "psychological" trauma, according to palliative-care specialists, Jennie Dear writes for The Atlantic.

Expand the scope of end of life care

Nessa Coyle, a nurse practitioner and palliative care leader, refers to the experience of recognizing one's own mortality as "'the existential slap.'" Based on her experiences with patients near death, Coyle said the realization often "precipitates a personal crisis," such as when a doctor discloses news of a terminal illness or a person sees how an illness has altered his or her appearance. "The usual habit of allowing thoughts of death to remain in the background is now impossible," Coyle said. "Death can no longer be denied."

How we process the realization of our own mortality

According to Dear, researchers and palliative care specialists have given the experience various names, such as "the crisis of knowledge of death," "an existential turning point," "existential plight," and an "ego chill." No matter the name, however, when confronted with ones own mortality people often experience similar mental and emotional realizations.

For instance, according to palliative care specialist Gary Rodin, the immediate effect of such awareness is the "first trauma"—the social and emotional effects of a given illness. Part of that trauma, according to Virginia Lee, a nurse who works with cancer patients, could stem from our cultural backgrounds. Lee explained that while most people intellectually understand the inevitability of death, people in Western culture, on an individual level, "think [they are] going to live forever," Lee said.

But when the realization hits, it "marks a radical change in how people think about themselves," Dear writes, citing E. Mansell Pattison, one of the first psychiatrists to write about the emotions of people who are dying. According to Pattison, humans "project ahead a trajectory of our life" and "anticipate a certain life span within which we arrange our activities and plan our lives.'" But death means that "our potential trajectory is suddenly changed."

People grappling with this crisis may experience "depression or despair or anger, or all three," Dear writes. People may question their beliefs or struggle with a loss of meaning. As one small Dutch study found, patients confronted with a diagnosis of incurable esophageal cancer reported that "their lives seemed to spin out of control."

And this existential crisis is often more trying than the physical illness, according to a 1970s study by Harvard researchers. For the study, researchers assessed the experience of newly diagnosed cancer patients with a prognosis of at least three months and found that for many, the existential crisis was more significant than their physical diagnosis. That said, most respondents said their "reckoning"—while "jarring"—was "relatively brief and uncomplicated," lasting two or three months. A few respondents, however, experienced lasting psychological problems because of the crisis, while others seemed to address it, then deny it and confront it all over again.

An evolving understanding

According to Rodin, palliative care doctors' understanding of patients' realization of death has evolved over time. While doctors previously thought patients were "either in a state of denial or … acceptance," Dear writes, paraphrasing Rodin, now, doctors think people fluctuate between the two states. "'You have to live with awareness of dying, and at the same time balance it against staying engaged in life,'" Rodin said.

And while striking that balance may not be easy, Dear writes that people who have gone through the experience of realizing their own mortality are often "better off because of it." Dear concludes, "These patients are more likely to have a deeper compassion for others and a greater appreciation for the life that remains"—but "to arrive there, they have to squarely face the fact that they're going to die" (Dear, The Atlantic, 11/2).

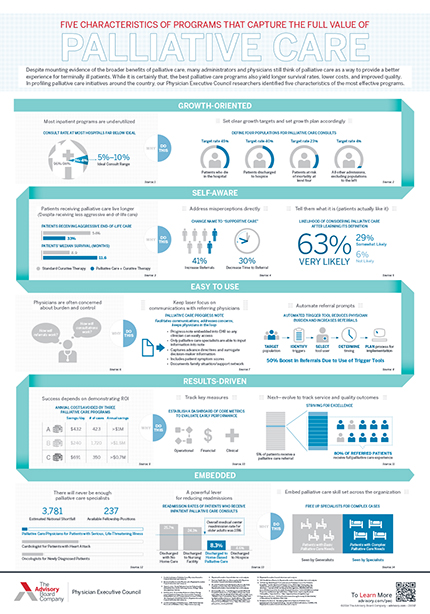

5 characteristics of programs that capture the full value of palliative care

What many don't realize is the best palliative care programs also yield longer survival rates, lower costs, and improved quality.

In profiling palliative care initiatives around the country, we identified five characteristics of the most effective programs.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.