Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutSome illicit drug users are relying on the heart rate monitors built into Fitbits, Apple Watches, and other wearable devices as "an early warning system" for overdose symptoms—but experts say the devices can lure drug users into a false sense of security, Christina Farr reports for CNBC.

'An early warning system'

Illicit drugs like cocaine can cause spikes in a user's heart rate, as the drug releases a large amount of dopamine into the body and create an adrenaline rush. That spike in heart rate is what some illicit drug users are monitoring using their wearable devices.

Farr spoke with one San Francisco-based tech worker, whom she refers to as "Owen," who began using his Fitbit to monitor his cocaine use about two years ago. He noticed the drug caused his heart rate to jump to 150 BPM, a rate that he usually only hits "if I'm running, like really intense physical activity," Owen said.

Owen said his Fitbit helps control how much cocaine he uses. When he notices his heart rate getting abnormally high, he knows it's time to skip a turn. "If someone says, 'Let's do a line,' I'll look at my watch," he said. "If I see I'm at 150 or 160, I'll say, 'I'm good.' That's totally fine. Nobody gives you a hard time."

While Owen acknowledges that the device's readings may not always be accurate, he believes it still provides insight into what's happening inside his body. "I don't really know what's happening in my body when I smoke some weed or do some cocaine," he said. "I can read information online, but that's not specific to me. Watching your heart rate change on the Fitbit while doing cocaine is super real data that you're getting about yourself."

Owen's story is not unique, Farr reports. She notes that a growing number of people describe similar experiences online. One user on Reddit by the name of 3meopcpnumberonefan said, "Drugs are basically the only reason I wear a Fitbit. I want an early warning system for when my heart's going to explode."

Representative from Fitbit and Apple declined CNBC's request for comment.

Experts warn against the practice

Medical experts generally agree that cocaine, even in small and infrequent doses, is dangerous—and warn that wearables may give some drug users a false sense of security.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that more than 5,000 people die from cocaine-related overdoses each year. According to Farr, some of those death are tied to angina, heart attacks, and strokes—conditions wearables do not necessarily monitor. Research also has shown that the heart rate trackers in wrist-mounted wearables are less accurate than the monitors in a standard chest strap.

Ethan Weiss, a cardiologist and associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, explained some vital signs that can be affected by cocaine use, such as heart rhythm and blood pressure, aren't able to be tracked by wearables.

"Taking drugs is always a risk, whether you're monitoring a tracker or not," he said. "It's possible this is leading people to do more cocaine" (Farr, CNBC, 7/9).

Your telehealth cheat sheet on wearables

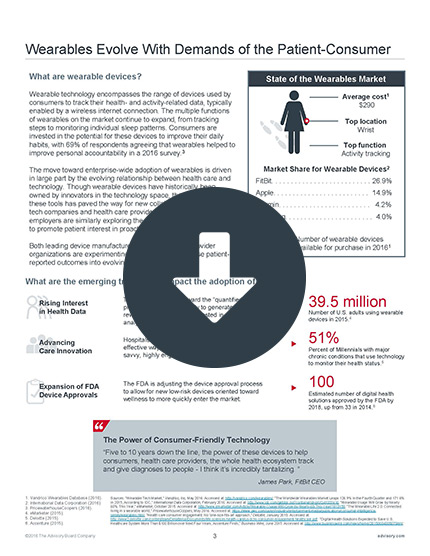

As the multiple functions of wearables on the market continue to expand, consumers are becoming more invested in the potential for these devices to improve their daily habits. Wearable technology can help to facilitate patient activation and improve clinical outcomes.

The cheat sheet details how rising interest in health data, advancing care innovation, and expansion of FDA device approvals has impacted the adoption of wearables.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.