Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutLong after the polio vaccine stemmed the disease that once infected thousands of people, a handful of U.S. polio survivors still rely on decades-old iron lung machines to stay alive—and must overcome increasing obstacles to maintain the devices, Jennings Brown reports for Gizmodo.

About the iron lung

Iron lungs were a staple in hospitals in the 1940s and 1950s, when poliomyelitis—a highly contagious disease that can paralyze a person's arms, legs, and respiratory muscles—was rampant in the United States, Brown writes. In 1952 alone, polio paralyzed 21,269 people and killed an additional 3,145. Children under five are particularly vulnerable to the disease.

For polio survivors who have difficulty breathing on their own—or who can't breathe at all—an iron lung is a critical survival tool. It's essentially a large metal tube that encases a person's body from the neck down and works by creating negative pressure that induces a patient's lungs to take in oxygen.

In 1955, the polio vaccine became available in the United States and largely ended the spread of the disease. By 1961, there were just 161 reported cases of polio in the United States. In 2016, there were just 37 cases reported worldwide, all in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

A handful of users

Though the polio vaccine largely eliminated the disease and the need for iron lungs, a handful of polio survivors are still dependent on the aging, difficult-to-maintain machines for survival.

Post-Polio Health International in 2013 estimated that six to eight iron lung users remained in the United States. Brown this fall interviewed three such individuals, who he writes "are among the last few, possibly the last three" iron lung users in the country.

Martha Lillard, age 69, contracted polio in 1953 when she was five years old. Today, she sleeps inside the machine every night, Brown reports.

Mona Randolph, age 81, contracted polio in 1956, at age 20. She initially used an iron lung for about a year before weaning herself off with rehabilitation, but she had to resume using the machine two decades later after several bronchial infections. She spends six nights a week in the machine.

Paul Alexander, age 70, contracted polio in 1952, when he was six years old. Alexander, who is nearly completely paralyzed, brought his iron lung to law school and became a trial lawyer. Now, he is in the iron lung almost constantly, Brown reports.

"Once you live in an iron lung forever, it seems like, it becomes such a part of your mentality," Alexander said. "Like if somebody touches the iron lung—touches it—I can feel that."

Maintenance challenges

For iron lung users, keeping the machines functioning is truly a matter of life and death, Brown reports. One polio survivor who relied on an iron lung died in 2008 when she lost power during a storm.

Electrical outages are not the only concern—maintenance also presents a significant challenge for iron lung users, Brown reports.

March of Dimes provided and serviced iron lungs until the late 1960s, when demand for the machines diminished. Around that time, J.H. Emerson stopped making new machines, and responsibility for maintaining old machines was handed off via a series of acquisitions and mergers.

Finally, in 2004, Respironics—which then handled maintenance for the devices—reportedly presented iron lung users with three options: adopt a newer ventilator device, continue using the iron lung with the knowledge that Respironics might not be able to fix it, or take full ownership and responsibility of their machine.

For many iron lung users this meant finding someone who would be able to help repair their machines. Fortunately, Lillard, Randolph, and Alexander each were able to find help in "generous, mechanically skilled friends and family," Brown reports.

Alexander, for instance, was connected with man who does safety testing on products and worked on iron lungs as a side project; Lillard has had her machine fixed by a friend who does custom metal fabrication; and Randolph's husband, an engineer, and her cousin, a mechanic, handle her machine's repairs.

But, according to Brown, replacement parts for the iron lungs, such as the collar that seals around a user's neck, have become scarce and costly.

Lillard said she began using Scotch guard around her existing supply of collars after she paid more than $200 each for two replacement collars from Philips Respironics, which currently handles maintenance for the devices, and learned that the company only had 10 left in stock. Philips Respironics declined to comment on the article, Brown reports.

When asked what happens if the supply runs out, Lillard said, "Well, I die."

Iron lung users urge polio vaccination

In interviews, all three iron lung users expressed concern about the anti-vaccine movement, which some public health experts say could result in another polio outbreak, Brown reports.

Richard Bruno, a clinical psychophysiologist, and director of the International Centre for Polio Education, said, "Parents today have no idea what polio was like, so it's hard to convince somebody that lives are at risk if they don't vaccinate." Bruno noted that if an individual with polio were to visit an area where many children aren't vaccinated against the disease, "then we could be talking about the definition of a polio epidemic."

Alexander said, "Now, my worst thought is that polio's come back." He added, "If there's so many people who've not been—children, especially—have not been vaccinated... I don't even want to think about it."

Lillard separately said, "I would just do anything to prevent somebody from having to go through what I have."

Similarly, Randolph said, "When children inquire what happened to me, I tell them the nerve wires that tell my muscles what to do were damaged by a virus. And ask them if they have had their vaccine to prevent this. No one has ever argued with me" (Brown, Gizmodo, 11/20).

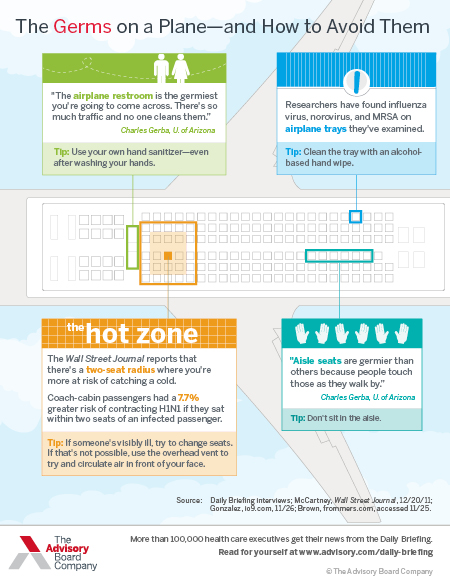

It's that time of the year again: How to avoid the flu when you fly

We spoke with the University of Arizona's Chuck Gerba—a microbiologist and expert in "fomites," or inanimate objects that are capable of spreading disease—about some of the most alarming hot spots on a plane, and the measures travelers can take to protect themselves. It was a mildly terrifying conversation.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.