Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutThe following article is an exploration of health care’s path forward from the perspective of a fictional senior leader in the year 2030. It is a companion piece to "Dispatch no. 2: Technology made health care better'and worse."

My fellow health care leaders,

Greetings from the year 2030. I need you to know some things about the decade ahead. Things that will change health care as you know it. Things I wish I had paid more attention to, and better understood, back in 2021. There's a lot our sector could have gotten right if we knew then what we know now.

I am sending you—via fax machine—a series of dispatches to help you better prepare for your future.

The message of my first dispatch is this: the population aged, as expected, but it was the aging of young people that changed health care in the most surprising ways.

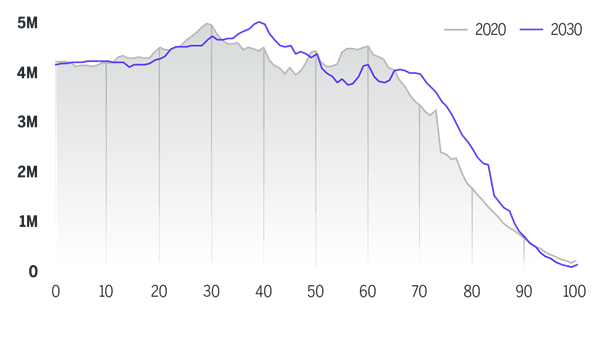

In 2030 (my present day), baby boomers are 65 and older, mostly retired, and requiring high levels of nursing and medical care. The industry was ill-prepared for this moment, despite its long-discussed inevitability. But as it turns out, the force of impact brought about by the aging of younger generations is proving equally significant, and harder to solve for. The intergenerational and intragenerational shifts in economic, familial, and political influence during the 2020s have reshaped the context for health care operations and strategy in ways that extend far beyond the growing population of septuagenarians.

U.S. population by age—2020 vs. 2030

Looking back on the past decade, below are 3 of the most important ways aging—and its broader demographic implications—has changed health care.

01

We incurred unexpected costs by prioritizing convenience

The de-centering of the doctor-patient relationship has come into conflict with the mounting health needs of Generation X and Millennials, many of whom increasingly require longitudinal, in-person care. Our industry’s aggressive moves to offer extraordinary convenience have over-valued the role of consumer preference—and by consequence, under-valued the role of clinician expertise—in strategy and investment decisions. Ironically, the inundation of tech-first, consumer-centric care models have created a diffuse and fragmented delivery landscape in which it is harder—not easier—for patients to make health-related decisions.

Since 2020, telehealth firms, consumer-oriented primary care companies, and other disruptors have continued to grab headlines and investment dollars. In particular, funding for digital health companies skyrocketed during (and following) the Covid-19 crisis. At face value, these bets made sense a decade ago, as they were predicated on conventional wisdom about consumer trends. Millennials and Gen Z were demanding swift access from their providers; many patients were shunning doctors who offered poor digital experience; people of all ages finally became open to using telehealth; and younger generations were less concerned with health data privacy than their parents.

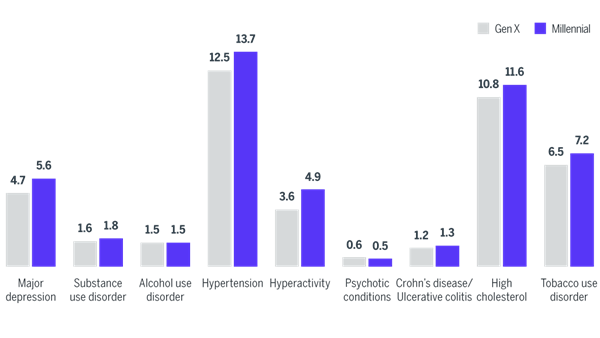

For many, these tech-first models offered an exciting proposition—and in truth, they have made life easier for many Gen Zers, Millennials, and even older generations. But these solutions weren’t right for everyone. In fact, they failed to meet the needs of millions—particularly those who required more traditional care. Convenience-driven models underestimated the amount of acute, in-person treatment that many Millennials and Gen X members now need, as they exhibit worse physical and behavioral health indicators than their parents and grandparents did at the same points in their lives. Specifically, major depression, hyperactivity, and type II diabetes had the largest growth in prevalence among Millennials from 2014–2017 and continued to worsen over the next decade. These deteriorating health outcomes are attributable to higher stress, poor diet, low levels of physical exercise, and growing social inequity—among other factors.

Digitally driven models also mistakenly treated younger generations as monoliths, assuming all members were able to use digital-first, self-directed care. As a result, disruptive care providers exacerbated digital inequities—especially among Millennials, who have experienced unprecedented levels of intragenerational socioeconomic inequality.

Prevalence rate comparison for top 10 conditions between Gen X and Millennials at the same age (34–36)

02

A critical consumer segment went largely overlooked

The “sandwich generation”—the cohort of adults providing financial, physical, and emotional support for both their children and aging relatives—has grown precipitously. And multigenerational housing reached its highest levels since the 1950s. In hindsight, we should have been far more intentional and careful to study the needs and experiences of these individuals. Doing so might have helped us get the shift to home-based care right. Instead, family caregivers quietly became the most important consumer segment that no one paid attention to.

This year, 2030, the youngest baby boomers are turning 66 years old. As they exited the workforce, they also began developing high rates of chronic health problems including heart disease, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease, which you are already anticipating. These age-related vulnerabilities led to greater dependency on their adult children.

At the same time, young adults continued to delay having children until their late 20s and 30s. The confluence of these patterns caused the so-called sandwich generation to grow larger than ever. The proportion of U.S. adults identifying as caregivers rose from 18.2% in 2015 to 21.3% in 2020, and has ballooned even more over the last decade.

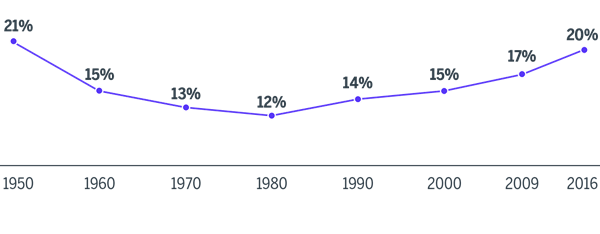

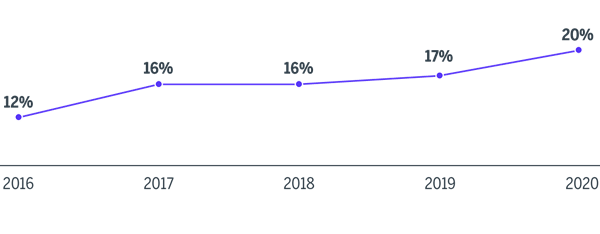

Multigenerational living also reached its highest levels since the 1950s, creating conditions for more adults to support their young children and aging parents. Pre-pandemic, this housing trend was already apparent, as the share of multigenerational U.S. households had crept up from 12% in 1980 to 20% in 2016. This shift was the combined result of financial distress that Millennials experienced in the Great Recession of 2008 and the increasing racial diversity of the population (immigrants and non-white people are more likely to live in multigenerational households). The move toward multigenerational living arrangements intensified post-pandemic due to the rise of the work-from-home economy, financial insecurity and job loss among young adults, and heightened fear among aging adults of moving into traditional nursing homes after watching their parents and grandparents suffer during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Percentage of U.S. population living in multigenerational households

For many individuals in the sandwich generation, things have not exactly been easy. Adult caregivers have had to make significant financial, career, and relationship sacrifices in order to adapt to their families’ multifaceted needs. Many of their parents were ultimately unable to afford long-term care. And even when direct health expenses were covered by Medicare or private insurance, caregivers often bore significant costs that weren’t covered, including those related to food, medication, transportation, housing, and the indirect expense of time not spent working. In 2020, 69% of adult caregivers paid for related expenses out of their own daily budgets, while 40% contributed less toward their savings accounts and 30% contributed less toward their retirement accounts due to their caregiving duties. These economic hardships compounded across the 2020s and contributed to worsening physical and mental well-being for caregivers, a growing share of whom are women and Black and Latino Americans who were already experiencing wage gaps.

Perhaps the biggest missed opportunity was in redesigning home-based care in ways that both seized the opportunities embedded in a growing generation of caregivers and rose to the challenge of making sure that those caregivers were not overburdened by responsibilities they could not fairly carry. Instead, caregivers were pushed to their limits by coordinating care across fragmented care settings and modalities, not to mention transporting their loved ones to and from appointments, even though persistent infrastructural barriers to home care began to erode. The sandwich generation would have jumped at the opportunity to facilitate more affordable and convenient home-based care for their loved ones, had we invested in them and made true regulatory and payment changes within the home care space.

03

The most vocal calls for change came from within our own workforce

Driven by their generational politics, diversity, and timing of their entry into the medical profession, young(er) clinicians have developed a less restrained—occasionally confrontational—relationship with the health system they animate. At times characterized by collective action, and at others by individual activism, doctors and nurses are exercising their social and political capital in ways that were only just starting to emerge back in the late teens and early twenties.

As you know, a significant percentage of your current clinical workforce is actively planning for retirement. Back in 2019, nearly 45% of active physicians in the United States were age 55 and older. In 2030, the youngest of those doctors are now 65. And thanks to Covid-19, many decided to leave the field even earlier than expected.

Unfortunately, rebuilding the pipeline of new clinicians has been no easy task, thanks in no small part to the demographic cliff we hit in 2025. While Millennials remain the largest generation by population size, they have had record low birth rates, which means there are fewer young adults today to fill roles in the clinical workforce. This clinician shortage is occurring at a time when our aging population needs ever greater levels of care.

While overall workforce supply remains a challenge, we have made progress in certain regards. For instance, newer clinicians are more racially diverse. That’s in part a natural by-product of broader demographic realities among younger generations, which are more non-white than baby boomers or the silent generation before them. But it’s also due to growth in medical school interest among people of color, specifically Black and Latino Americans, a trend that accelerated during the pandemic you’re living through.

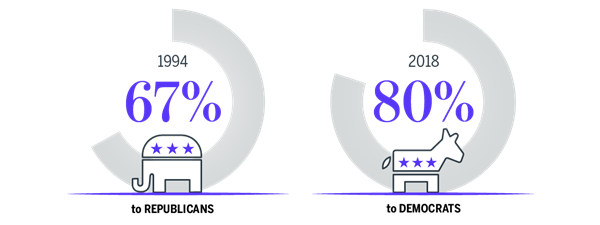

As Millennials and Gen Z joined our industry’s ranks across the past 10 years, they have furthered a political realignment of the clinical workforce that began decades prior. Back in 2019, 48% of incoming medical students identified as liberal, 33% identified as moderate, and 19% identified as conservative. I recall that even as early as 2018, more than 80% of political contributions from physicians favored Democratic candidates and campaigns. At the time, that was nearly a complete reversal from the 1990s, during which doctors were largely aligned with the Republican party. A majority of doctors in your time, albeit a smaller one, favored a single-payer health system in the United States. This reality gave us moments like the American College of Physicians’ support for single-payer health care in early 2020, and the near-simultaneous softening of the AMA’s opposition to Medicare for All.

Physicians' political campaign contributions over time

In addition to growing support for coverage and payment reform, today’s clinicians have a heightened sense of empowerment to outwardly agitate for change. And this doesn’t just apply to voting dynamics or political contributions. In fact, they are expressing their views through more activist means. The number of unionized health workers has swollen, as have the membership ranks of advocacy groups on medical school campuses and among working professionals. For example, in 2020, students from Harvard Medical School created the first chapter of Future Doctors in Politics, a nonpartisan organization that shows medical students how to get involved in shaping policy and even run for public office. Organizations like this have only become more prevalent across the 2020s. At the same time, a large and growing number of clinicians began using social media platforms to make their views heard on a range of issues—from public policy debates, to medical misinformation, to their employment satisfaction.

Unionization rates among registered nurses in the U.S.

The consequences of this shift are now on full display. Personal politics aside, few of us truly predicted the extent to which calls for major health policy reform would be loudest from within our own workforce. Organizational leaders from your time struggled to proactively anticipate and respond to calls for change made by your clinical employees. As for those doctors and nurses today, well they’ve never been more frustrated with our slow pace of change, justifiably or not.

Fellow leaders—if you are reading this letter, please know that you are not too late. The story I’ve just told you should alarm you, but this future is not (yet) written in stone. You can still depart from your current course. And if you do, what I’m describing will become nothing more than the shadow of a future you purposefully avoided.

Until next time,

Anonymous

SOURCES

- “Age and Sex Composition in the United States: 2019,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2019.

- “Healthcare 2030: The Consumer at the Center,” KPMG, 2019.

- “The Health of Millennials,” BCBS, April 24, 2019.

- Kohn D et al., “A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households,” Pew Research Center, April 5, 2018.

- Boston-Fleischhauer C, A Primer on Nurse Labor Organizing,” Advisory Board, April 21, 2021.

- Abrams A, “A New Generation of Activist Doctors Is Fighting for Medicare for All,” Time, October 24, 2019.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.